FLIGHT OF THE MAGPIE

We caught up with the artist behind our latest bespoke signage, Alastair Mooney, to talk about his practice, time and the magic that results from it.

We caught up with the artist behind our latest bespoke signage, Alastair Mooney, to talk about his practice, time and the magic that results from it.

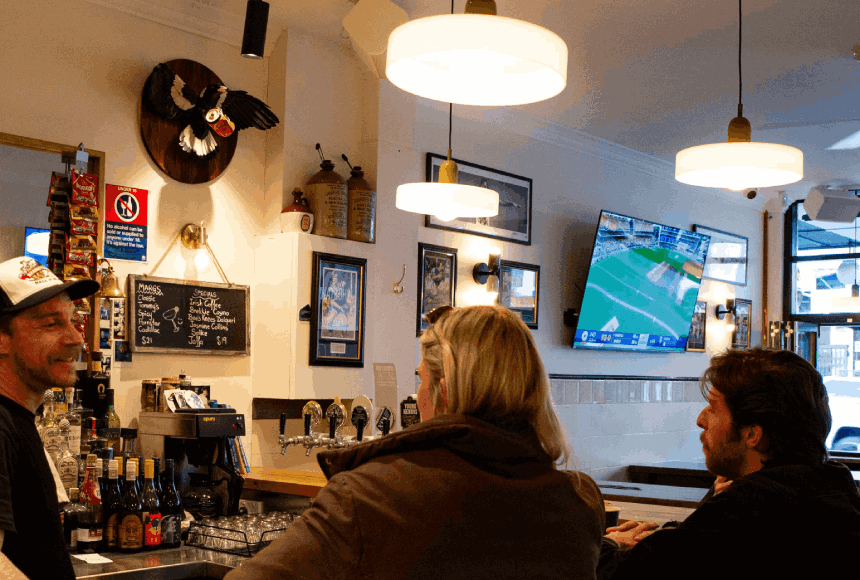

You might’ve only glanced at the magpie sculpture in the pub of the same name on

Enmore Road. You may have even taken a moment to admire the detail and noticed

the entire bird is carved from wood.

What you probably don’t know is that this masterpiece was hand carved, delivered and installed by artist Alastair Mooney, all the way from regional Tasmania. And what you can’t have appreciated in your brief appraisal is the sheer scope of time tied up in this stunning artwork.

When Alastair Mooney left Tassie to attend art school in Melbourne, he never thought he’d return. So, nine years later, he was surprised to feel the itch to go back – which he succumbed to scratching. Still more surprising was finding himself moving from painting into carving, choosing to use a unique timber endemic to the island: huon pine.

‘Go into any souvenir shop in Tasmania and the smell of it will hit you in the face immediately,’ he tells me, in a soft voice embodying the wood he works with and the patience needed to do so. Huon’s high oil content is what gives it that singular aroma, meanwhile making it easy to work with and finish as beautifully as it smells: ‘I’ve had issues with people wanting to touch my sculptures in the past. So there’s this tension in the work – you want to touch it but you aren’t allowed.’

It quickly becomes apparent that Alastair could wax lyrical about huon pine all day. ‘Huon has almost folkloric, mythical properties. It’s coveted like gold in this state.’ Alastair tells us, ‘People hoard the stuff, and it’s only getting rarer.’

He talks about how it grows exclusively on the West Coast and South West Tasmania. How only those with a special permit can harvest it, from the litter of previously felled trees that are scattered about forests and waterways. How much of this wood was cut down over 100 years ago by loggers for ship building, because the material is naturally waterproof and doesn’t rot. How this practice has since been outlawed for sustainability, due to how slow-growing the tree is. ‘I’ve seen a tree that’s 2000 years old…’ he says in wonder.

Now fiercely protected, huon pine is one of the oldest living organisms on earth. Individuals can survive up to 3000 years, and clusters cloning from the same original tree can survive over 10,000 years. Even the block the magpie sculpture comes from would’ve been cut down around 150 years ago, Mooney estimates. This age is what gives the wood its distinctive grain, visible in the magpie on the top of the can it clutches: ‘I've made pieces before where in an area the size of a 20 cent coin, you can see 200-odd growth rings.’

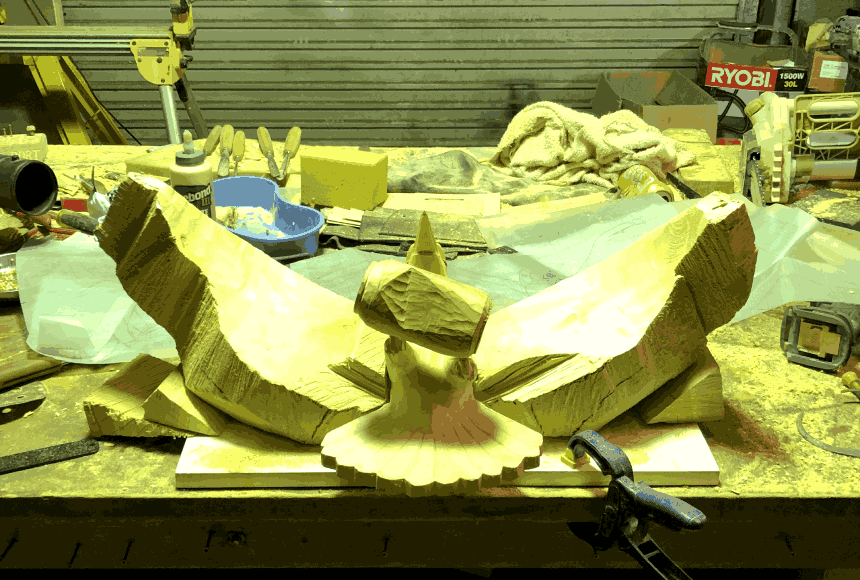

Mooney’s reverence for the material he uses not only makes sense but feels important to his practice. Carving a sculpture as opposed to molding means that, in a lot of cases, mistakes can’t be undone: ‘you can't cut too deep, because then you've spoiled the form.’

Working with such a precious material demands care and respect, something he’s cultivated over more than a decade. Beyond the time taken to develop his own craft, every piece Mooney makes is born through many hours. And the magpie is a prime example of this. ‘I stopped writing down the hours I spent working on it towards the end, but I figured out it took about 130 hours, spread over nearly nine months.’

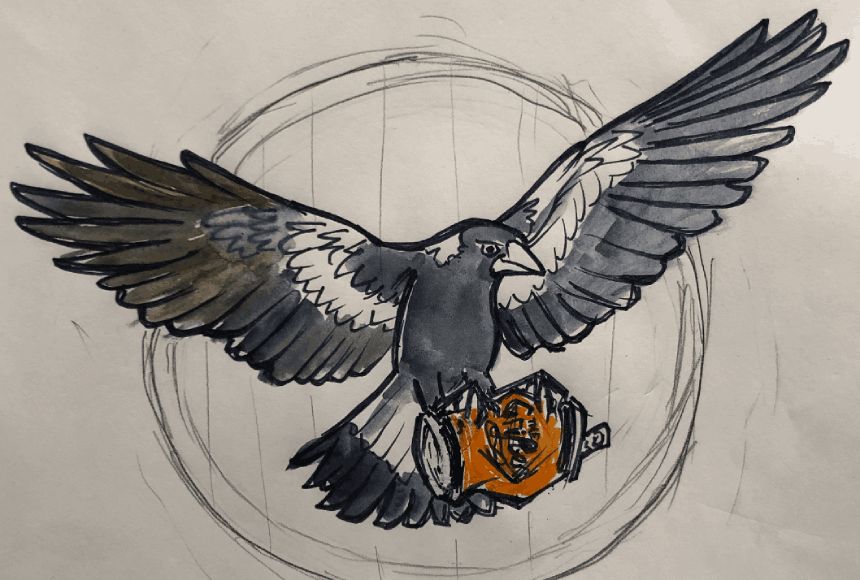

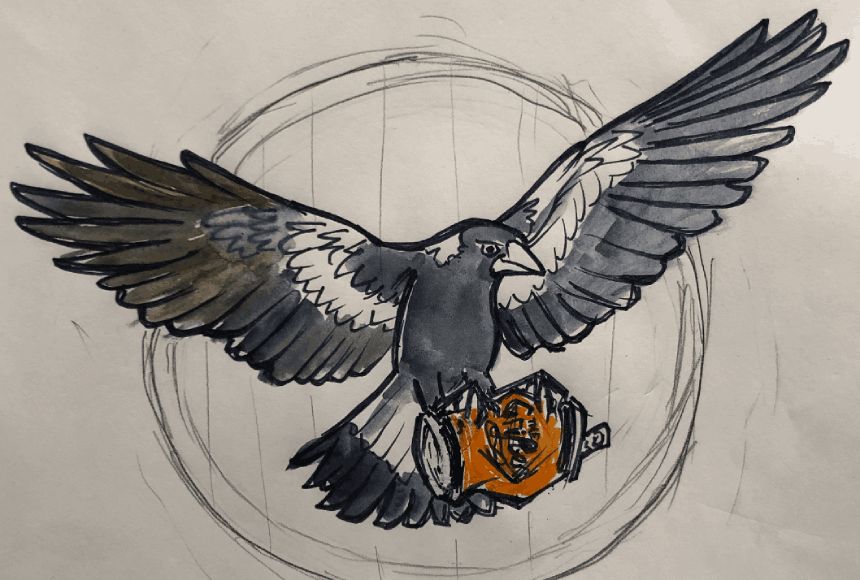

A batch of Pale takes around two weeks to brew and package before a can finds its way into the clutches of a thirsty consumer. They’ll then polish this off within the space of a few minutes, discarding the vessel with little thought. That’s why Mooney finds the can motif (as seen crushed within the magpie’s grip) such an engaging one to work with. There’s a fascinating interplay in depicting an image so fleeting, through months and months of labour, via a method finessed over years, using a material that might’ve taken millenia to grow.

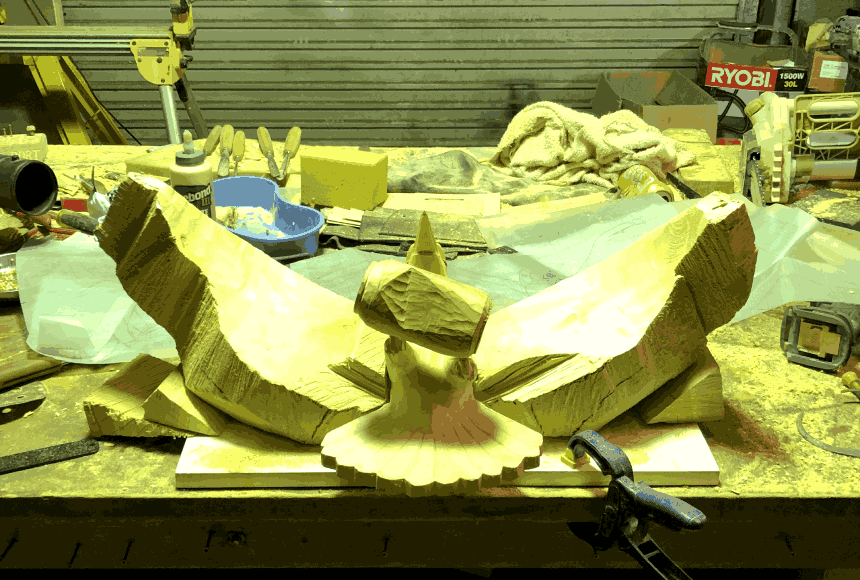

‘I'd say it's the most intricate piece I've ever done,’ Mooney states, proudly. The magpie’s particular swoop was part of what made this sculpture so painstaking. ‘I sculpted every feather in a different pose. So it was probably the most challenging work I've ever done, too.’

In order to capture the dynamic gesture, Mooney needed to use three separate bits of wood, all cut from the same huon block. ‘It's a magpie, so obviously it had to be black and white. I don't usually stain my works, but it was fun to do something different for this one.’

Standing out against the monochrome are the magpie’s striking red eyes, marking a first in Mooney’s work. ‘This is the first time I've used taxidermy eyes in a sculpture, which I love. They're translucent, like real eyes, and they look schmick from every angle. So, I’ll definitely be using them again in future works.’

Finally, it isn’t the Pale can alone that makes this work distinctly Grifter. ‘I love the amount of bird action in the Grifter beer graphics, which was a strong visual reference for the spread-winged swoop of the magpie. The decision to make a circular backboard was also inspired by a beer coaster; the brand has a great aesthetic, besides the tasty brews!’

Mooney went to Melbourne with ambitions of becoming a painter. But after arriving at the Victorian College of the Arts, he was soon pulled in a different direction. ‘I realised I wasn't very good when I got to art school and there were all these mind-blowing painters there. But even in the painting department, I would make more sculptural, physical forms, which I was much more drawn to.’

That’s what makes works like the magpie not only something you can observe, but interact with. ‘Rather than a two-dimensional thing – a picture of something that exists somewhere else, whether that be real or a fictional scene or whatever – a three dimensional object exists on your plane, in the room you’re walking around. And that creates a much deeper response.’

With this in mind, Mooney is excited about setting the magpie free; it now hangs majestically at The Magpie of Enmore. ‘I’d been working on it in solitude for so long. So there was a feeling of relief and excitement about seeing it on the wall. There's definitely an element of worry, as the sculpture’s protection is no longer in my control. But that fades soon enough. And a lot more people will get to enjoy it up there than in my studio.’

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience.